Lewis Harrison: Civil War Vet & Homesteader

Lewis Harrison was born Lewis Tandy around 1842 in Todd County, Kentucky. From his early years as an enslaved person to becoming the only known African American homesteader in Houston County, Minnesota, his journey marks a significant chapter in the region's history.

Early Life and Enslavement

Lewis Tandy was born around 1842 in Todd County, Kentucky. Likely enslaved under Dr. Mills Tandy, Lewis worked as a farmer, facing the harsh realities of enslavement in southwestern Kentucky. These early experiences shaped Lewis’s character and resilience.

Civil War Service

On September 24, 1864, Lewis enlisted in the Civil War, joining Company A of the 13th Heavy Artillery, United States Colored Troops (USCT). At 25 years old, he was described as having a yellow complexion, brown eyes, and black hair. Initially serving as a teamster, Lewis’s role transitioned to orderly duties at regimental headquarters from February to May 1865. He continued his service at Rendezvous Headquarters in July 1865, Regimental Headquarters in August 1865, and the Quartermaster Department in September 1865. He was honorably discharged on November 18, 1865, in Louisville, Kentucky.

From Lewis [Harrison] Tandy’s military paperwork. In the remarks section he is listed as a new recruit from Todd [County, KY] who owed service to Dr. Mills Tandy.

Journey to Minnesota

After the war, Lewis moved to Minnesota and adopted the surname Harrison. On July 12, 1869, he applied for a homestead in Houston County under the Homestead Act of 1862. His application, numbered 5913, required a fee of $11. By May 1870, Lewis Harrison had settled on the land, breaking and fencing about 12 acres, transforming it into a productive farm.

Creating a Community

By the June 1870 census, Lewis had established a small community on his land. Living with him were his wife Delilah, her children Maggie and Cary, and their child together, Fanny. Other residents included Absalom Wallace, a 52-year-old laborer from Virginia, J.B. Brown, a 23-year-old laborer, Martha Brown, a 19-year-old from Norway, their son Willis Brown, and Mary and Susan Wallace. This small but vibrant community of African Americans within a predominantly white region. Maggie and Cary attended the local school, integrating into the white town. However, by 1875, only Lewis, Delilah, and their three children remained on the homestead.

1870 Census - Houston Co., Minnesota

Lewis Harrison, his family, and the community of Black families living on his land.

Homesteading Challenges and Daily Life

Lewis faced numerous challenges on his homesteading journey. On September 19, 1876, he stated in a deposition, "for twenty-five years or thereabouts he has been and was a slave." This background contributed to his misunderstanding of some legal requirements, believing that residing on the adjoining land was sufficient. Despite these obstacles, Lewis's hard work paid off. Unable to read and write, he used an "X" mark to sign documents. Neighbors W. Romain Franklin and Stephen Jennings testified to his continuous residence and improvements, confirming he had cultivated about 12 acres since May 1870.

From Lewis Harrison's Homestead Application. Affidavit states “that for twenty-five years or thereabouts he has been and was a slave.”

Land Patent and Legacy

On April 25, 1877, Lewis obtained his land patent, Number 4426, for 40 acres in Union Township, Houston County, Minnesota. This marked the culmination of his efforts and determination, with the final receiver's receipt fee costing $7.

Life After the Homestead

By 1880, Lewis and his family had moved from their homestead into Hokah village in Houston County, where Lewis worked as a laborer. The census listed him as 49 years old, with parents from Kentucky and Maryland. Delilah was noted as being 38 (seemingly aging backwards, a common trend for women reporting their age), Cary was 17, and Fannie, who attended school, was 8. In Hokah, Lewis owned two lots of land, demonstrating his continued commitment to providing for his family and establishing a stable home. This ownership is documented in a map from that period, highlighting his property in the village.

A New Chapter in La Crosse

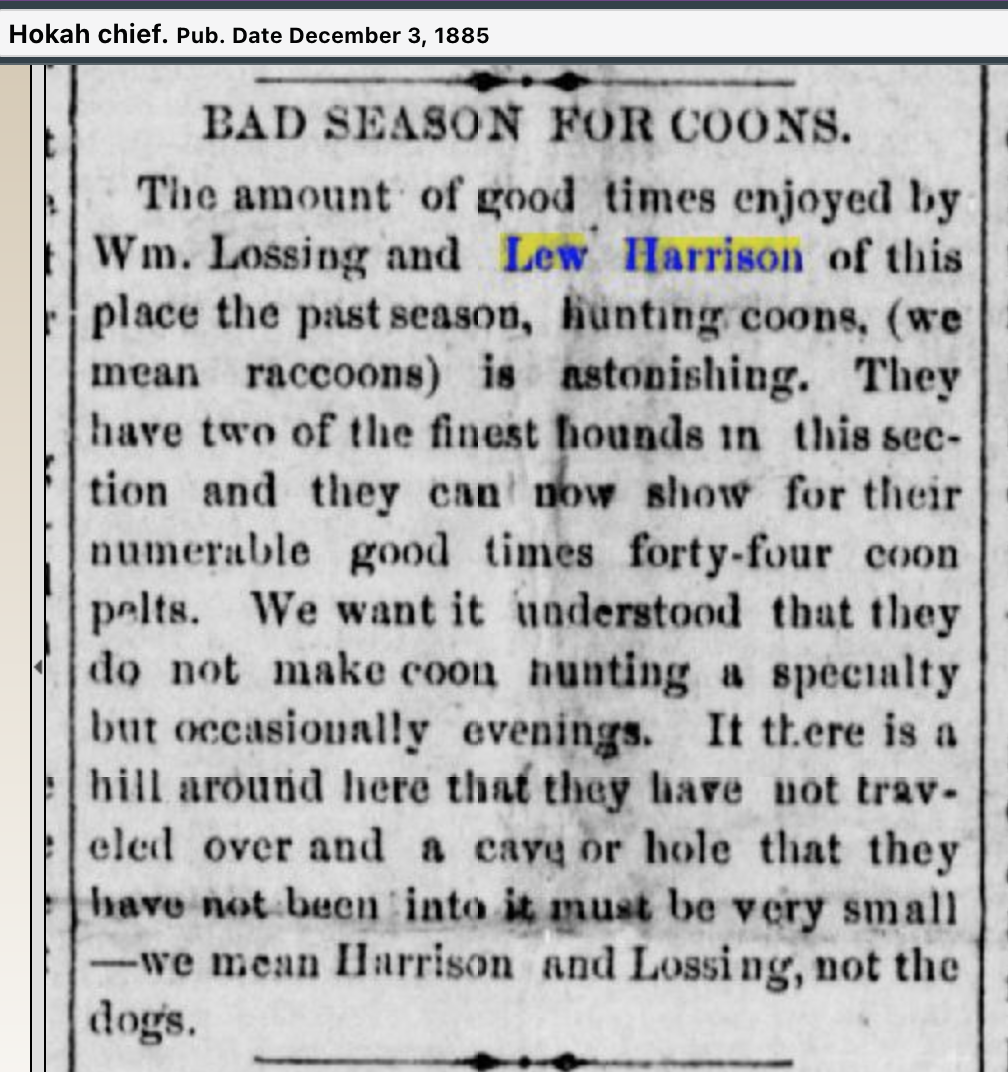

In April 1884, a newspaper article stated, "Lew Harrison will shortly move to LaCrosse." But in 1885, Lewis, Delilah, and Fanny were still living in Hokah, Houston County. In December 1885, a Hokah newspaper reported on Lewis's success in raccoon hunting with Wm. Lossing, showcasing his integration and activity within the community yet not-so-subtly adding racial undertones.

In 1886, another newspaper article noted, "Lew Harrison has a good paying job in La Crosse and as a result his family will move over in a few days." By March 18, 1886, the Hokah newspaper reported, "Lew Harrison and family moved to La Crosse Monday. Hokah is nearer a white town now than it has been for years."

Community Life and Recognition

In January 1888, a newspaper mentioned, "Lew Harrison and wife of LaCrosse drove to our village yesterday with the nobiest [SIC] turnout in the city." This highlights Lewis's established status and presence in the community, indicating a level of success and respect. In April 1888, another article noted Lewis's visit to bid farewell to friends, contemplating a move to Washington Territory. This reflects his ongoing connections and the possibility of seeking new opportunities, showing his adaptability and continued ambition throughout his life.

By November 1896, Lewis had moved back to Hokah from Missouri, making the trip by team and occupying the Bentz place in upper town. In November 1897, a newspaper article described Lewis's participation in a promotional event in La Crosse, where he dressed in a soldier's uniform to attract attention to a saloon's display. In December 1897, Lewis married Emma Smith, a colored woman from La Crosse, further establishing his ties in the area.

Final Years

By 1900, Emma was listed as widowed in the census. She was living with her mother, Clara Johnson, and her children, all with the last name Smith, likely from her marriage to Mr. Smith.

Lewis’ death date and his final resting place remain unknown. Further research continues to try and find him and ensure he has a proper Civil War veteran headstone at his grave site.